I don’t go to movies much anymore. Most of them just aren’t worth the inconvenience. Mostly, I go only when “She” gets bored and wants to do something together. After years of reading and writing and lecturing about films, of seeing movies because I had to, there is a glorious freedom to being able to pick and choose and to simply watch movies, rather than having to actually “think” about what I have seen.

That doesn’t mean I don’t see movies – lots of them – but simply to say that I see them when and under whatever conditions suit me, not the marketers, and I don’t feel obligated to comment on them. Still, years of habit kick in and I find it impossible not to think about important films or to attempt to communicate to others what I saw in them.

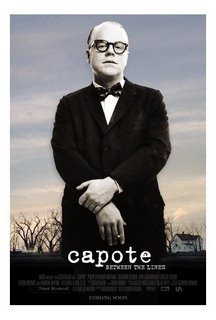

The other night, at a friend’s insistence, I finally watched “Capote.” It is, so far, the only one of the Oscar nominated films I have seen. I’ll probably wind up seeing the rest, but in my own time. For now, “Capote” has given me a lot to chew on.

What to say? What to say?

It is, first of all, a profoundly conservative film.

Quite early in the story “Capote” establishes a moral dichotomy -- drawing a stark contrast between the shallow, vicious, sophistication of

In this regard I was reminded of Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” — specifically the scenes portraying the elite intellectual milieu to which Marcello Mastroianni’s character aspires, but which is eventually revealed as brutally, even inhumanly, sterile and destructive.

But what about the technical aspects of the film? That’s what everyone raves about!

The ravers are right. “Capote” is brilliantly acted. Chris Cox, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, and Clifton Collins -- all are at the top of their games. There isn’t a weak performance in the entire film. Hoffman’s portrayal is one of the great ones in modern cinema. The cinematography, by Adam Kimmel, is also first rate and rivals that of Connie Hall in the earlier film. The set design, the costuming, the soundtrack, all are perfect. I lived through that era, and couldn’t find a missed beat anywhere. To use a term popular back in those halcyon days of youth: “Kudos,” to Bennett Miller and the entire production team.

How about its intellectual content?

The film works well on a number of levels. It is a savage portrait of the manipulative monster Truman Capote became in the course of his celebrity. It perfectly captures the mood of the Kennedy years, one of the most depressing periods in our nation’s history. And it raises important questions about the relationship between art and humanity.

There is no doubt that “In Cold Blood” was an important book and by far Capote’s best output. I had forgotten over the years just how well he wrote. Hoffman’s reading of the opening paragraphs of “In Cold Blood” reminded me of Capote’s power as a prose stylist. But in the pursuit of that masterpiece, Hoffman’s Capote discards every vestige of humanity and in the end stands revealed as a cruel, insane, vicious monster.

Capote was caught in what most would consider a terrifying dilemma – he has some power to aid Smith and Hitchcock, the condemned murderers, to keep them alive for a while and to offer them something approaching companionship. He does this, playing the part of a sympathetic friend, so long as their continued existence on this earth and their good will serves his need to gather information for is book. But eventually it becomes clear that he needs an execution to provide closure to the story he is writing. How will he respond to this moral dilemma?

It is agonizing to watch Capote lying to and coldly manipulating his subjects, especially Perry Smith, knowing that their lives are forfeit in the end. Does he pay an emotional price for his sins? Yes, but that doesn’t really deter him. Capote’s response to moral agony is withdrawal and abandonment! He regresses into an infantile state, curling into a fetal position, crying incessantly, refusing to leave bed, consuming large amounts of alcohol and baby food, leaving his victims to wonder what happened to their great friend and benefactor as death looms closer.

Finally, propelled by shame and the knowledge that his narrative requires closure, Capote returns to the prison to witness Smith and Hitchcock’s demise. In many films this agony could serve as a basis for redemption, but not here. “In Cold Blood” was a triumph, but it also marked the end of Capote’s literary career; he never produced anything of significance after that. Instead he lapsed ever further into nasty, infantile, cruel, and alcoholic posturing that made him such a sensation in mid-century Manhattan’s smart literary set. In the end he became little more than a bad joke -- one of the most grotesque figures in that pitiful milieu.

Counterposed to the loathsome Capote was Perry Smith, one of the condemned men he pretended to befriend and care for. The movie loads the dice emotionally by portraying Perry sympathetically – presenting him as a sensitive, questing intellect and talented raw artist (not that different from Capote) who had never gotten the breaks his famous “friend” had. In a way I found this disturbing and suspect that Robert Blake’s interpretation of the same character was much closer to the real thing [I did not see the TV version, but hear that it was quite good]. Blake’s sort of portrayal, though, would not have served the dramatic purposes of this film because sympathy for Perry was necessary to highlight the reptilian, exploitative nature of Capote’s character.

I was interested to see that “Capote” [again building verisimilitude while advancing the story] indulges in one of the overwhelming intellectual conceits of the mid-twentieth century – that deviant personalities were inevitably a result of bad upbringing. One of the critical conventions of the time was that characters had to be made psychologically interesting by explaining their motives through past abuse. Here we get it in spades. At one point Capote establishes a bond with Smith by indulging in a horrendous competition over who had the worse childhood. Capote, the more articulate of the two, wins. Here in these two monstrous persons we see the early manifestations of today’s “cult of victimization.”

The relationship between Smith and Capote forms the spine of the narrative. We come to sympathize with Smith, seeing him almost as he does himself, as a sensitive victim, and his sudden revelation near the end of the film that it was he, not the loutish Hitchcock, who set off the killing spree comes like a slap across the face. Here the film achieves its emotional peak and forces us to contemplate the question of which figure, the self-deluding Smith or the manipulative Capote, was the real monster in the relationship. In the end, the film’s judgment is that they both were. Smith and Capote were, as Hoffman explains, twisted twins who had walked through different doors in life.

Nearly as important to the film is the relationship between Capote and Harper Lee, brilliantly portrayed by Catherine Keener, his companion through most of it (Jack Dunphy appears only in interludes). I was tempted to see Ms. Keener’s character as the moral center of the film, because it is she who finally confronts Capote with his essential inhumanity, but I was wrong to think that. A friend of mine (formerly a screenwriter, now a professor) pointed out in an e-mail that Lee enthusiastically, even gleefully, abetted Capote’s manipulation of the good people they met in

On a philosophical level the film raises the question of the relationship between art and humanity. The conventional explanation is that art represents or comments on the human condition, but in this film the act of creating art necessarily distances the artist from his subject and the relationship between them is revealed as ultimately exploitative. The artist is a parasite, feeding on the agony of his subjects and excreting…, art. It is to Capote’s credit that he understands this, even as he ruthlessly applies it, and that he himself experiences some degree of moral agony and shame. And it is this fact that raises “Capote” to the level of true tragedy. Hoffman’s character had the opportunity to rise above his milieu and to become a real human being – instead he remained a prisoner of his milieu and degenerated into a mere artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment