In the light of widespread protests against the Pope's recent remarks, I thought it might be useful to note the section of his address in which they occurred. Here is the relevant excerpt from the official Vatican transcript:

I read the edition by professor Theodore Khoury (Muenster) of part of the dialogue carried on -- perhaps in 1391 in the winter barracks near Ankara -- by the erudite Byzantine emperor Manuel II Paleologus and an educated Persian on the subject of Christianity and Islam, and the truth of both. It was probably the emperor himself who set down this dialogue, during the siege of Constantinople between 1394 and 1402; and this would explain why his arguments are given in greater detail than the responses of the learned Persian. The dialogue ranges widely over the structures of faith contained in the Bible and in the Koran, and deals especially with the image of God and of man, while necessarily returning repeatedly to the relationship of the "three Laws": the Old Testament, the New Testament and the Koran. In this lecture I would like to discuss only one point -- itself rather marginal to the dialogue itself -- which, in the context of the issue of "faith and reason," I found interesting and which can serve as the starting point for my reflections on this issue. In the seventh conversation ("diálesis" -- controversy) edited by professor Khoury, the emperor touches on the theme of the jihad (holy war). The emperor must have known that sura 2:256 reads: "There is no compulsion in religion." It is one of the suras of the early period, when Mohammed was still powerless and under [threat]. But naturally the emperor also knew the instructions, developed later and recorded in the Koran, concerning holy war. Without descending to details, such as the difference in treatment accorded to those who have the "Book" and the "infidels," he turns to his interlocutor somewhat brusquely with the central question on the relationship between religion and violence in general, in these words: "Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached." The emperor goes on to explain in detail the reasons why spreading the faith through violence is something unreasonable. Violence is incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul. "God is not pleased by blood, and not acting reasonably ("syn logo") is contrary to God's nature. Faith is born of the soul, not the body. Whoever would lead someone to faith needs the ability to speak well and to reason properly, without violence and threats.... To convince a reasonable soul, one does not need a strong arm, or weapons of any kind, or any other means of threatening a person with death...." The decisive statement in this argument against violent conversion is this: Not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God's nature. The editor, Theodore Khoury, observes: For the emperor, as a Byzantine shaped by Greek philosophy, this statement is self-evident. But for Muslim teaching, God is absolutely transcendent. His will is not bound up with any of our categories, even that of rationality. Here Khoury quotes a work of the noted French Islamist R. Arnaldez, who points out that Ibn Hazn went so far as to state that God is not bound even by his own word, and that nothing would oblige him to reveal the truth to us. Were it God's will, we would even have to practice idolatry. As far as understanding of God and thus the concrete practice of religion is concerned, we find ourselves faced with a dilemma which nowadays challenges us directly. Is the conviction that acting unreasonably contradicts God's nature merely a Greek idea, or is it always and intrinsically true? ....Read the entire address here. [offending phrase emphasized by me]

It is clear that Benedict was not himself attacking Islam. Rather he was asserting that conversion through violent means was against the will of God. But this was not how the text was received in the Muslim world.

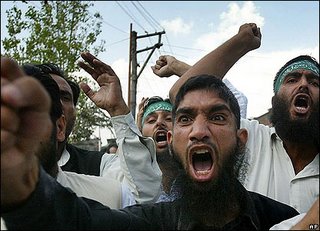

Rather predictably Islamic radicals ginned up widespread protests against the offending words that (also predictably) turned violent. [here]

My first reaction, as that of many others, was repulsion at the Islamist response. That was just the sort of violence that the Pope was denouncing, and anyway that kind of protest had jumped the shark back in the cartoon controversy. It doesn't impress me any more.

Predictably, the NYT blamed the Pope for his remarks rather than the Islamists for their violence:

There is more than enough religious anger in the world. So it is particularly disturbing that Pope Benedict XVI has insulted Muslims, quoting a 14th-century description of Islam as “evil and inhuman.”Read it here.

This constitutes nothing less than a deliberate misreading of the Papal statements, no less objectionable than the ravings of the Islamists. Once again the NYT has covered itself in shame.

Anyway, today the Vatican issued a statement that in part reads:

The Holy Father thus sincerely regrets that certain passages of his address could have sounded offensive to the sensitivities of the Muslim faithful, and should have been interpreted in a manner that in no way corresponds to his intentions.Read it here.

This has heen construed by some sources, notably the BBC, as an abject apology. [here]

Others have argued that it is nothing such. [here]

Anyway, whatever the case, Muslim leaders have said that the "apology" will not be sufficient to stem the tide of Islamic outrage [no surprise there].

And so it goes..., and so it goes...., ho hum. I've seen this movie before and the scenario jumped the shark a long time ago.

Unnoticed in the whole controversy, however, is that the Pope's condemnation of conversion through violent means could be taken much more aptly as a critique of current US policy in the Middle East than as an insult to Islam. But such an interpretation, in today's political and media environment, would be surprising.

No comments:

Post a Comment